RaaS: The Rapid Growth of The Ransomware-as-a-Service Business Model

Cybercriminals are driven by the profit motive, and few activities are more profitable to them than deploying ransomware against unsuspecting businesses.

Ransomware is a type of malware that uses encryption to block or limit users from accessing systems–such as databases, file servers or applications–until a ransom is paid. Ransomware attacks have risen sharply in the last couple of years, so much so that the United States and other G7 countries this year pledged to work together “to urgently address the escalating shared threat from criminal ransomware networks.”

Why has ransomware proliferated? Clearly, a shortage of cybersecurity professionals experienced in dealing with these types of attacks has something to do with it. But there is another, even bigger factor at play here: the growth of Ransomware as a Service, or RaaS.

How the RaaS model works

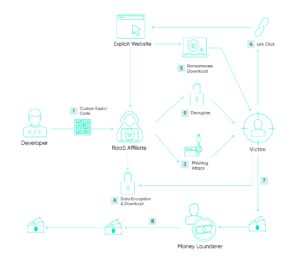

Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) is the evil twin of the Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) business model, whereby the software provider (in this case, the ransomware developer) leases their software (the ransomware) to customers (other cybercriminals) who then use the ransomware to attack businesses.

RaaS providers use a range of revenue models, including one where the provider receives a percentage of every ransom payout and their customers (known as “affiliates”) keep the rest. RaaS providers recruit affiliates on the dark web and take payment in cryptocurrency. Some RaaS groups even provide manuals on how to use the malware, 24/7 customer support, and ransom payment management.

The RaaS model benefits malware developers in a number of ways. It keeps developers one step removed from the actual ransomware attacks, allowing them to maintain some form of anonymity or deniability. It allows them to focus on improving their ransomware while their affiliates focus on distribution. And most importantly, it is scalable: the top ransomware developers have hundreds or even thousands of cybercriminals doing their bidding for them–which, in a nutshell, is why ransomware has become so lucrative.

RaaS examples and variants

Like viruses, ransomware is constantly evolving, and new strains and variants are formed all the time. Prominent examples include:

- DarkSide – a Russian-speaking RaaS group believed to be acting independently of state actors but with the implicit support of the Russian government. Formed in 2020, DarkSide started off attacking Windows devices but has since expanded to include Linux capabilities as well. It is best known for the May 2021 ransomware attack on the Colonial Pipeline in the U.S., which temporarily shut down 45% of East Coast fuel supply and earned the hackers a $4.4 million ransom payment.

- REvil (aka Sodinokibi) – a Russian-speaking RaaS operation believed to be associated with DarkSide. In July 2021 it hacked the computers of a contractor that works with the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and NASA, and published stolen documents on its Happy Blog. Revil’s most successful attack from a financial perspective was the one it launched on Brazil-based meat processing company JBS S.A., which earned the ransomware developer and its affiliates around $11 million. REvil was itself hacked and forced offline in October 2021 by a multi-country operation led by the United States, according to Reuters.

- Ryuk – initially believed to be from North Korea, but is now suspected of being run by multiple Russian criminal cartels. Ryuk’s code targets the Microsoft Windows cyber-systems of large public entities, either through phishing campaigns that contain links to malicious websites or attachments with the malware. Ryuk made $61 million from ransoms in 2018-19, according to the FBI. In November 2020, it forced the Baltimore County Public School system, which serves 115,000 students, to temporarily shut down classes.

- LockBit – another RaaS provider that uses affiliates to attack its targets. Designed to attacked Windows systems, its greatest strength is its ability to spread autonomously through a network after manually infecting a single host. LockBit’s most prominent recent victim was Accenture, a multinational professional services company that ironically specializes in IT services. Accenture said there was no impact from the attack, but reports from numerous sources have claimed that the attackers published thousands of files to the Dark Web.

- DoppelPaymer (aka Grief) – first appeared in 2019 when it launched attacks against organizations in critical industries. It is one of a number of major RaaS groups that threatens to publish their victims’ data unless a ransom is paid (known as a “double extortion” attack. DoppelPaymer went quiet around the time of DarkSide’s ransomware attack on the Colonial Pipeline but has since reappeared and rebranded under the “Grief” name. Its ransom demands range from $25,000 to $1.2 million.

The rapid rise of RaaS (and how it can be stopped)

We’ll probably never know the exact impact of ransomware. After all, attackers don’t publish annual reports, and victims would often prefer to conceal embarrassing payments–unless, of course, they are a publicly traded company and are required by law to disclose these things to shareholders.

What we do know for sure is that ransomware attacks on businesses have risen sharply in the last two to three years. Chainalysis, a private firm that tracks transactions to blockchain, says at least $350 million in ransom payments were made in 2020. The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaints Center (IC3) received a record 2,474 complaints about ransomware in 2020, with a combined $29.1 million in losses from ransom payments. But as the FBI itself acknowledged, the actual losses from ransomware are much higher, due to the fact that victims don’t always report any loss and that its calculations don’t includes lost time, wages, and equipment.

Although attacks on big corporations capture the headlines, 23 percent of small businesses and 43 percent of businesses overall reported being the targets of cyber-attacks in 2020, according to a study commissioned by specialist insurer Hiscox of businesses in the United States and seven other countries. Sixteen percent of firms reporting a data breach were hit with a ransomware demand, and 58% of these firms paid a ransom at a median amount of $11,900. A separate study of ransomware attacks against more than 300 American SMBs by NetDiligence, a cyber risk assessment specialist, found that the average ransom demand was $12,000 and the median demand was $81,000.

The good news is that RaaS groups can be stopped if–and it’s a big if–there is no financial incentive. As TechRepublic recently noted, the response from governments in the wake of the Colonial Pipeline attack led to the banning of ransomware groups from Russian forums on the Dark Web where they recruited affiliates. This in turn reduced the profitability of the ransomware-as-a-service as a model and led to a temporary lull in attacks.

Bottom Line

Ransomware–whether in the form of RaaS or future models–will be around for as long as criminals get paid. In an ideal world, organizations would stop giving in to the demands of RaaS groups and the financial incentives of carrying out ransomware attacks would simply disappear.

In the real world, your organization can do a number of practical things to mitigate the threat of ransomware, starting with the use of robust anti-spam filters to reduce the likelihood that phishing emails will reach users. Another way your organization can avoid becoming a victim of ransomware is through the use of a managed security operations center (SOC). A good SOC monitors your critical infrastructure in real-time, enabling rapid incident response and narrowing the attack surface before it spreads beyond your control.